China: Almost gone but not forgotten

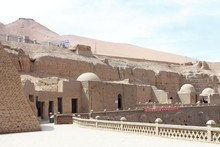

The Bezeklik Thousand Buddha caves are the work of the Uighur people. Photo / Jim Eagles

The most moving thing about the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha caves, in a remote corner of China’s Xinjiang Province, is that there is little left to see.

When they were created 1000 years ago, these shrines must have been stunning. But now, although the caves themselves are still there, the statues and frescoes with which they were decorated have mostly gone.

They were stolen, as the guardian bitterly explained, by Western archaeologists. And, he added, much of what was not stolen was destroyed. Only fragments now remain to show the splendour of the work.

The caves are the work of the Uighur people who moved into the area about 1000 years ago. Their first efforts were dedicated to the Manichaeism they brought with them from Central Asia. But, following the Uighurs’ conversion to Buddhism, the vast majority celebrated Buddhism scriptures. When Islam arrived, work on the caves ceased and some Muslims even destroyed faces and gouged out eyes because of the prohibition on human figures.

The caves lie along a river gorge, amid a spectacularly desolate landscape, squeezed between the red rocks of the Flaming Mountains and the endless sands of the Taklamaklan Desert.

But if you take the path that leads unpromisingly down the steep side of the gorge suddenly a whole new world opens up, with rows of doorways leading into the cliff face, and occasional glimpses of colourful frescoes or flowing sculptures.

There are apparently 77 caves altogether, though some have collapsed and many are closed to the public, but the few we were allowed to see served to create the impression of a picture of a great treasure tragically lost.

The first cave we entered was clearly intended to have statues at the back. The space was empty.

The walls were decorated with figures of kings and gods, monks and warriors, flowers and animals, but in several places large chunks, perhaps 30cm square, had simply been cut out.

Bin, our Chinese guide, said the pieces of fresco had been removed about a century before by the German archaeologist, Albert von Le Coq. “He took them back to Berlin to put into museums and they were destroyed in the bombing in World War II.”

When he left, Le Coq smeared the walls with mud in the hope of preventing other archaeologists from finding the pictures, Bin added. “Our archaeologists have tried to remove the mud but it is too hard. They used a special technique to remove it from that one there,” he said pointing, “but as you can see it didn’t work.”

By the look of it the process used to remove the mud had also removed most of the paint. “They are not going to clean any more paintings until a better technique has been found,” said Bin.

Another cave had been so badly desecrated the walls were almost completely bare. Instead, hanging here and there were prints of some of the pictures that once covered the bare mud, copies from the pieces in German museums before they were bombed.

Some caves, however, did have their frescoes more intact. In one was an impressive depiction of the moment when Buddha reached nirvana. The reclining Buddha figure that was supposed to have been the centrepiece was missing, taken by the Hungarian-British archaeologist, Sir Auriel Stein, but the fresco behind where the statue once stood still showed people of many nationalities, some mourning his departure, others celebrating his achievement.

Along the side of the cave were more pictures which, according to Bin, showed the donors who had made construction of the cave possible, some holding out money, others bearing platters carrying gifts of food. But one figure was missing. “It was taken by a Japanese.”

It was much the same story in each cave we visited: a few delightful scenes from the life of Buddha, or of kings and gods conversing, or – the theme that gave the caves their name – of thousands of Buddhas looking down on the world dispassionately, just to whet the appetite, and beyond that empty plinths, blank spaces, crumbling plaster, walls smeared with mud or bare rock.

I have since seen photos of the caves in books and on the internet – although we were not allowed to take any pictures inside – and it does seem that some of the caves we were not allowed into do have more of their pictures still intact.

Nevertheless, memories of the visit to those caves remains for me a rather moving memory, with admiration for the work of the Uighur artists rather overwhelmed by anger at the damage done to their creations.

CHECKLIST

Getting there: Singapore Airlines operates 12 times per week between Auckland and Singapore and then onward to 62 destinations in 34 countries, including China.

Getting around: World Expeditions operates its Silk Road expedition from Beijing to Samarkand via Bezeklik in April, May, August and September. Ring 0800 350 354 for more details.

Jim Eagles visited China with help from Singapore Airlines and World Expeditions.

http://www.nzherald.co.nz/travel/news/article.cfm?c_id=7&objectid=10706361