Uyghur Asylum Seekers

The internationally recognized rights of asylum seekers have been consistently flouted by the Chinese government for decades, primarily in relation to neighbouring states. Uyghur asylum seekers have been forcibly deported from states with strong trade and diplomatic ties to China for many years.

The act of forcibly repatriating individuals or groups who make it clear about their desire not to be returned to their home country is a clear infringement of well-established international law. The non-refoulement principle spelled out in the 1951 Refugee Convention—to which China is a state party—requires that states do not allow for the forcible return of refugees or asylum-seekers to territories where their “life or freedom would be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, member of a particular social group, or political opinion.”

Historical Flight of Uyghurs from East Turkistan

Historically speaking, the Chinese government has shifted its approach towards Uyghur out-migration over the years depending on factors including the attitudes of its leaders, activities of the population, and in response to major events. Our current focus will be to develop a better understanding of the Communist Party’s most recent attitude towards Uyghurs who have fled over the last 3-4 years in particular. Despite sporadic openings over the last several decades in the ability of Uyghurs and others to move in an out of the country, the internationally recognized rights of refugees and asylum seekers have been mostly ignored by the Chinese government.

Amnesty International began documenting cases of Uyghurs who were forcibly returned to China in the late 1990s, many of whom had already been registered by the UNHCR as asylum seekers. This trend was immediately noticeable following the attacks on 11 September 2001, which provided China with a handy new vehicle to justify repression of certain communities. Amnesty documented cases of Uyghurs being returned from Nepal, at least seven from Pakistan between 2002 and 2004, as well some from as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

In one highly visible and controversial case, a Canadian citizen, Huseyincan Celil, was arrested while visiting family in Uzbekistan in 2006 and was subsequently deported to China. His case brought international attention and elicited strong objections by the Canadian government. Celil fled China back in 2001 following a short jail term for his support for religious and political rights Uyghurs and now remains in prison in Urumqi. During the ordeal, he was denied access to legal counsel and Canadian officials, his dual citizenship was not recognised, and was forced to sign a confession which led initially to a life sentence (his sentence has since been reduced to 20 years).

In the years that followed, Uyghurs have been forcibly returned from a number of other states. In December 2009, 20 were returned to China from Cambodia, even after the group were in the process of having their asylum claims reviewed by the UNHCR. Only days following the extradition, China and Cambodia signed 14 trade deals worth around 1 billion USD. Another five were returned from Pakistan and eleven from Malaysia in August 2011, and another six again from Malaysia in what Human Rights Watch called, “a grave violation of international law” in 2013. In addition to the above mentioned cases, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Burma, and Nepal have also extradited Uyghurs to China and since 2001 at least 289 Uyghurs have been forcibly deported.

Current Cases

Since 2014, there has been an intensification of these efforts which culminated in the return of 109 Uyghurs on 8 July 2015 from an immigration detention facility in Bangkok, Thailand, despite widespread condemnation from the international community. The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) had reportedly been given assurances by Thai authorities that those in detention would be safe from persecution, as the group made it plainly clear that they did not want to be deported. Although it was reported that the Thai government sent a delegation to China in order to check on the state of those returned, no official report or statement was ever released concerning the state of the group or their whereabouts.

The deportation came after months of deliberations and pressure to ensure that a number of Uyghur groups, who had fled around the same time to both Thailand and Malaysia, would not have their rights under the Refugee Convention contravened. It was reported on 13 March 2014 that a group of 62 Uyghurs were arrested by Malaysian border control personnel while attempting to cross into Thailand on the northern border. Around the same time, another 200 were found in a human smuggling camp in southern Thailand and were transported to an immigration detention facility in Bangkok. Additionally, another group of 155 Uyghurs were found crammed into two tiny apartment units in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, on 1 October 2014, and were subsequently transported to the Kuala Lumpur International Airport Immigration Detention Depot.

The July deportations came on the heels of Turkey’s acceptance of 173 Uyghurs from the same facility in Bangkok, suggesting that the move may have been in direct response to that action. This approach also indicates the likely intention of the Thai government to appease both the international community and their call to observe international law on the one hand, and heavy pressure from China—a major economic partner—on the other. The ostensible justification given by the Chinese government was that the group was made up of “illegal immigrants” who should therefore be rightfully returned to China in the meantime. As of early 2016, a group of around 50 Uyghurs remain in the Thai facility waiting to have their citizenship verified.

Consequences of this kind of treatment have included arbitrary arrest and detention, abuse, and typically involves dubious criminal charges leveled against those who are returned. The Chinese government has repeatedly called such escapees criminals and all those who are returned have been treated in such a manner in the past.

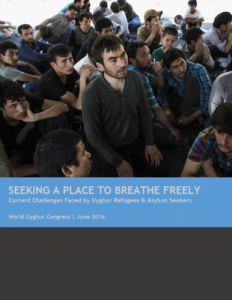

Seeking a Place to Breathe Freely: Current Challenges Faced by Uyghur Refugees & Asylum Seekers

Following extensive first hand research working directly with Uyghur refugees and asylum seekers who fled to Turkey from East Turkestan, the WUC has published a comprehensive report detailing current conditions in the region as well as the narratives of those whose escape lasted many months. The report, Seeking a Place to Breathe Freely: Current Challenges Faced by Uyghur Refugees & Asylum Seekers, offers a unique, first-hand glimpse into conditions seldom reported and scarcely heard by the international community until now.

Central to the report are the voices of those who decided that they were no longer able to bear the brunt of the repressive Chinese regime for so many years. We heard stories of men who were arrested and tortured for organizing cultural events, women arrested for wearing the hijab, and children who were left without parents after many were detained for indefinite periods.

The general feeling from all those whom we spoke with was of utter helplessness—a near total lack of autonomy or control over their own lives. State controls have become so intense in the region that many felt that they had little choice but to escape with the help of human smugglers.

We recount the vivid details of these clandestine journeys made through China, across the border into Southeast Asia and eventually onto Turkey—all of which have resulted in untold suffering including tremendous financial losses, long arrests, and the cold separation of family members throughout.

The report then looks better understand the motivations behind the decision many made to leave. We were told that cultural and religious restrictions, severe controls on freedom of movement, arbitrary arrests and decrepit conditions and treatment in prison were some of the prime motivating factors. The interviewees were able to sketch a quite clear picture of what is has been like to live as a Uyghur for decades under increasingly strict controls by the Chinese government.

Additionally, the report looks to better contextualize issues faced by Uyghurs who have fled China. We looked to position the Uyghur refugee issue in relation to international law and some of the barriers that continue to persist that have made the Uyghur asylum process very tenuous.

Key recommendations derived from the report are as follows (more detailed recommendations are included in the report itself):

- China must observe international law and discontinue its harsh and inexcusable repression of the Uyghur population in East Turkestan – particularly those who have been unjustly detained in the past and continue to face severe consequences upon their release.

- The UNHCR must continue to develop a competent interstate supervisory body to hold states accountable if they fail to meet their protection obligations under the Refugee Convention.

- UNHCR officials must recognize the severity of the situation among Uyghur refugees and the consequences faced by those who have been returned in the past.

- States on China’s border and extended periphery, particularly Thailand and Malaysia, must observe international law with regards to their handling of Uyghur refugees.

- Southeast Asian states in particular must take steps to ensure that rampant corruption witnessed by Uyghur refugees is rooted out.

- The Turkish government must recognize the rights of Uyghur asylum seekers who have landed in Turkey.

- Other states on China’s border to the west (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan) must uphold international law and ensure that political and economic considerations, namely the influence of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, do not trump international law.

The overarching goal of the report has been to overcome the persistent obstacle that impedes our understanding of how members of the Uyghur population in China are coping with state policies. It is our intention to make these findings available to all interested parties including those working in government or civil society, and the general public.

The report can be downloaded here.