Watched, judged, detained

CNN, 18 February 2020

Below is an article published by CNN, Photo NRD.

Ivan Watson, Ben Westcott — Rozinsa Mamattohti couldn’t sleep or eat for days after she read the detailed records the Chinese government had been keeping on her entire family.

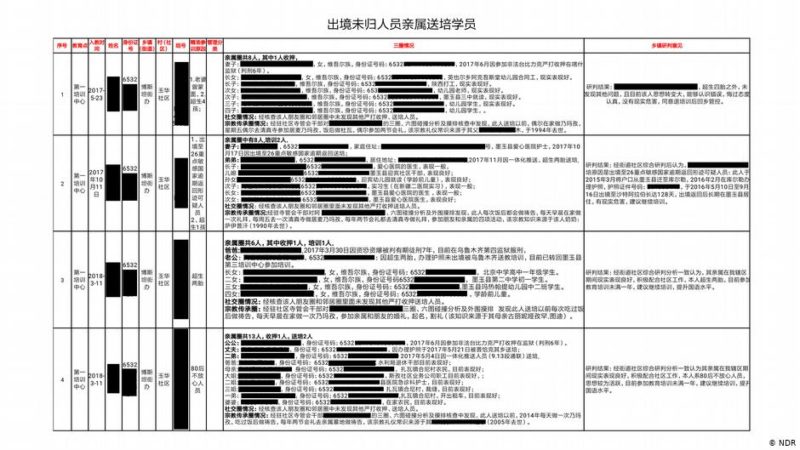

She and her relatives, most of whom live in China’s western Xinjiang region, aren’t dissidents or extremists or well-known. But in a spreadsheet kept by local officials, her entire family’s lives are recorded at length along with their jobs, their religious activity, their trustworthiness and their level of cooperation with the authorities. And this spreadsheet could determine if Mamattohti’s sister remains behind razor wire in a government detention center.

Her family’s records, and hundreds of government reports like them, have been leaked to journalists by a patchwork of exiled Uyghur activists.

The document reveals for the first time the system used by the ruling Chinese Communist Party to justify the indefinite detention on trivial grounds of not only Mamattohti’s family but hundreds — and possibly millions — of other citizens in heavily fortified internment centers across Xinjiang.

It is the third major leak of sensitive Chinese government documents in as many months, and together the information paints an increasingly alarming picture of what appears to be a strategic campaign by Beijing to strip Muslim-majority Uyghurs of their cultural and religious identity and suppress behavior considered to be unpatriotic.

The Chinese government has claimed it is running a mass deradicalization program targeting potential extremists, but these official records, verified by a team of experts, show people can be sent to a detention facility for simply “wearing a veil” or growing “a long beard.”

For Mamattohti’s sister, 34-year-old Patem, the crime for which she was detained, according to the document, was a “violation of family planning policy,” or put simply, having too many children. Under the countrywide policy, which rarely if ever is cause for imprisonment, rural families in Xinjiang are limited to three children. Patem had four.

It was the first time since 2016 that Mamattohti had received any concrete news of what had happened to her family.

“I never imagined that my younger sister would be in prison,” Mamattohti told CNN, through tears, in her house in Istanbul. She said she first saw the leaked records when they were informally circulated on social media among Uyghurs overseas. “As I was reading their names I couldn’t hold myself together, I was devastated.”

The leak exposes what appears to be a detailed and far-reaching system of state surveillance in the region, run by the local government in Xinjiang, designed to target Chinese citizens for peacefully practicing their culture or religion.

CNN has only been able to independently verify some of the records contained in the document. But a team of experts, led by Adrian Zenz, senior fellow in China studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington DC, say they are confident that it is an authentic Chinese government document.

The leaked document is a 137-page PDF file, likely generated from an Excel spreadsheet or Word table. Zenz pointed to the use of similar terminology and language in this document, which he refers to as the Karakax List, and other records leaked from Xinjiang.

He said the records showed that Beijing was detaining Uyghur citizens for actions that in many cases did not “remotely resemble a crime.”

“The contents of this document are really significant to all of us because it shows us the paranoid mindset of a regime that’s controlling the up-and-coming super power of this globe,” Zenz told CNN.

CNN sent a copy of the document to both the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the local government in Xinjiang, to see if they could verify its authenticity. There was no response.

Speaking in Germany on Thursday, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that he would gladly welcome any international diplomats or media to visit Xinjiang to see the truth for themselves.

“(Those who have come) have not seen any concentration camps or persecution in Xinjiang. However, what they have seen is that all ethnic groups are able to live peacefully and harmoniously … Their religious freedom is totally protected and they can practice their religion without any restrictions,” he said.

“The so-called concentration camps with so-called 1 million people are 100% rumors. It is completely fake news. I do not understand why these people are still lying while having the facts. I can only say that these people are deeply prejudiced against China.”

A previous attempt by CNN to visit the detention centers in Xinjiang was blocked by local government authorities.

The document: Family, neighbors, religion

China’s vast western region of Xinjiang has for centuries been home to a large population of predominantly Muslim ethnic groups, the largest of which is the Uyghur. Until recently, there were many more Uyghur citizens in Xinjiang than Han Chinese, the ethnic majority in the rest of the country.

Since 2016, evidence has emerged that the Chinese government has been operating huge, fortified centers to detain its Uyghur citizens. As many as two million people may have been taken to the camps, according to the US State Department.

Former detainees and activists say the facilities are actually designed for the purposes of re-education — places where inmates are forcibly taught Mandarin and instructed in Communist Party propaganda. Some testimonies from former detainees describe over-crowded cells, torture and even the deaths of fellow detainees.

https://edition.cnn.com/interactive/2020/02/asia/xinjiang-china-karakax-document-intl-hnk/