The Uyghurs’ Massacre of July 2009: A Survivor Remembers That Day in Urumqi

Bitter Winter, 5 July 2019

By Ruth Ingram – A Woman Remembers. Piles of human bodies waiting to be scooped up from the side of the road is Risalat’s enduring memory of July 5th 2009. But where these corpses had come from, who they were, and why there were so many, bullet-ridden and motionless in pools of blood on the street was a ghoulish mystery that only later she was able to piece together.

By Ruth Ingram – A Woman Remembers. Piles of human bodies waiting to be scooped up from the side of the road is Risalat’s enduring memory of July 5th 2009. But where these corpses had come from, who they were, and why there were so many, bullet-ridden and motionless in pools of blood on the street was a ghoulish mystery that only later she was able to piece together.

In the fading light of that memorable Sunday evening ten years ago, she hardly dared believe her eyes as she peered through a crack in the curtain from her vantage point on the thirteenth floor. As the bulldozers and diggers stood by, about to shovel them up and pile them high into waiting trucks, a single woman stood slowly clutching her baby covered in blood. Risalat still remembers the sound of her pitiful wailing.

Earlier that day, unbeknown to her, parts of Urumqi city had become a battleground. Chinese had been massacred by rampaging Uyghurs armed with knives and bricks, and that no one doubts. But what Risalat was witnessing, it later emerged, could be none other than a summary round up and execution by government forces of hundreds of perceived “troublemakers’.” To all appearances this could only be read as chilling payback after the afternoon’s events, to avoid the inconvenience of a mass trial.

What Really Happened

Official figures of 197 dead and 1700 injured following the riots were nothing but airbrushing, according to any Uyghur or Han spoken to on that day or since. Journalists visiting hospitals all over the city, were met with rows of bodies and doctors overwhelmed with the shear numbers of dead and injured.

But Risalat had witnessed something apart from simply the aftermath of the day’s mayhem. She said that what she saw was different. This was quite separate she said, and amounted to several hundred dispatched in cold blood. “Repeated all over the city, who knows how many thousand might have been executed,” she said.

Visitors Not Welcome

Ten years later that ghastly picture has still not left her. Recurring flashbacks still remind her of what she saw. A simple holiday back to see family and friends in Xinjiang, and arriving ironically on that very day, became a nightmare from which she wonders whether she will ever wake up.

Having become a British citizen and received her new passport, she decided to return home for a month to show off the children born to her in exile and to visit her parents. She arrived on a warm blue-skied summer’s day, parked her bags with relatives in downtown Urumqi and prepared for a trail of visitors to welcome her back. And came they did, gifts and food in hand, with embraces, smiles and tales of the years they had been apart. She was feted like a long lost friend. The city was looking particularly beautiful that summer, she remembers. Driving from the airport the flower displays were stunning, and she was looking forward to seeing her family and friends, tasting the unique locally produced home made ice cream, a speciality from her home town, and wandering around the many night markets to reacquaint herself with national delicacies, not easily prepared in her foreign kitchen.

She planned to stay with her sister in a modern high rise apartment right in the heart of a Uyghur neighborhood, not far from the iconic “Rebiya Kadeer” building, named after Beijing’s bête noir, the Uyghur human rights advocate now in exile in America. The area was a bustling mêlé of butchers, bakers and open air bazars, and Risalat was looking forward to wandering around and soaking up an atmosphere that life in the west was beginning to erase from her memory. But barely had friends started to trickle by, than rumors began to circulate of something terribly amiss around the city. Smiles soon turned to fear and the danger of having a “foreigner” in their house, albeit a former Chinese citizen, became apparent, once the scale of the unfolding horror began to emerge. Confirming their worst fears, around 5pm a call came from overseas asking if she was OK. News had already reached the outside world that something was happening. No sooner had the call finished than house phone lines were cut, friends left immediately and she and her three toddlers were put in a side room and ordered not to come out.

Western forces were later accused of stirring up discontent and anti-government sentiment in Xinjiang and non Chinese passports, even if they belonged to a former citizen, were immediately under suspicion. “When we were children America was always blamed for anything bad that happened in our country,”said Risalat. Police had been told to watch out for foreign infiltrators and journalists. Her arrival on that very day might have been seen as too much of a coincidence and those “harboring” her were in grave danger. Her sister told her to stay away from the window and not on any account to leave the apartment. No one must know she was there.

Painful Memories

Everyone has their own memories of “Qi Wu.” (The acronym for the July 5th riots) It was a defining moment in the history of Urumqi. Because the riots were spread randomly over the city, some people enjoyed their Sunday blissfully unaware of anything untoward. Their day of rest passed without incident. Only the next day did news start to seep through and the extent of the full ghastliness emerge. Others were caught up in the violence, unleashed it seemed because of frustration with government inaction over the assault by Han Chinese factory workers on two of their Uyghur female colleagues. Young people from all over the city converged on the People’s Square, but the peaceful student demonstration to demand action, spilled over when a number of Uyghurs infiltrated the crowd with knives and Molotov cocktails and this seemed to be the fuse which ignited the crowd to violence. The crowd of demonstrators became a mob that ran amok through the city.

Some people spent the afternoon trapped in burning busses, or forced to run for their lives, hiding behind shop fronts whose owners took pity on them. Stories of great bravery emerged as Uyghurs sheltered Han in their homes, and Han gave refuge to Uyghurs in the line of fire. Hundreds of Uyghurs joined the protest shouting, throwing bricks through shop windows, overturning cars and attacking Han Chinese. Mobile phone signals had not yet been turned off and video clips and photos flew around the world, giving those outside a horrifying picture of what was going on.

Later in the evening as they were eating, Risalat heard a loud bang and shooting. Rushing to the window they saw the area swarming with soldiers carrying automatic weapons. From her thirteenth floor vantage point all Risalat remembers is row upon row of her fallen countrymen, victims of random machine fire.

“ I saw hundreds of bodies, “ she said, still barely able to contain her grief ten years on. For three months she couldn’t erase the memory of those corpses.” The images just wouldn’t go away,” she sobbed, reliving the horror ten years later as if it were yesterday. From her small terrified corner of Urumqi she was seeing the dying throes of a day whose tragedy still scars the memories of all those who witnessed the violence.

Post-Traumatic Stress

She says she is forever rehearsing in her mind the events of that day, and trying to make sense of it all. She remembers thinking back, that she had seen a group of young people that afternoon walking past their apartment block in silence in the direction of the Peoples’ Square. A Uyghur youth was brandishing a Chinese flag, but they had all seemed orderly and peaceful. “Looking back, I realize these young people must have been part of the crowd that gathered that afternoon to protest,” she said. “We thought it a bit strange, but not much else until all the other terrible things started to happen.”

Around 9.30 pm, once the shots appeared to abate, a cousin decided to make a run for it. Ten minutes later she was back, wailing and beating her chest. Parked around the corner were two massive trucks spilling over with dead bodies. “We’re all done for,” she cried. “When will they come for us too?” She asked. More automatic firing ensued. No one could sleep. Around 1.30 am, a haunting “Allahu Akbar!” resonated through loudspeakers on the road below. Mere minutes later they heard more rapid machine gun fire. This had been a trap Risalat later realized, to lure the remaining “troublemakers” onto the streets. This same scenario was repeated half an hour later. More shooting.

Some time later all was quiet. They dared to look through the curtains. Police vehicles and army vehicles were everywhere and all that could be heard was the swish, swish, swish of high pressure hoses cleaning buildings, streets and even trees. “I will remember that sound until my dying day,” she said. “Every trace of blood and human remains were wiped clean. Swish swish swish for hours through the night.”

The next day dawned deathly silent. “People were stunned and everyone was too afraid even to mention that dark night to their neighbors,” she said. Local government officials gave out free bread and vegetables and told people to stay at home and government TV was full of anti-American, “anti-separatist” propaganda and interviews with the “heroes” who had stood up against the splittists.

Only a few days later did anyone dare to ask about the disappeared, many of whom were children or husbands, friends of friends or relatives who had gone missing that night. Most have never come to light even now.

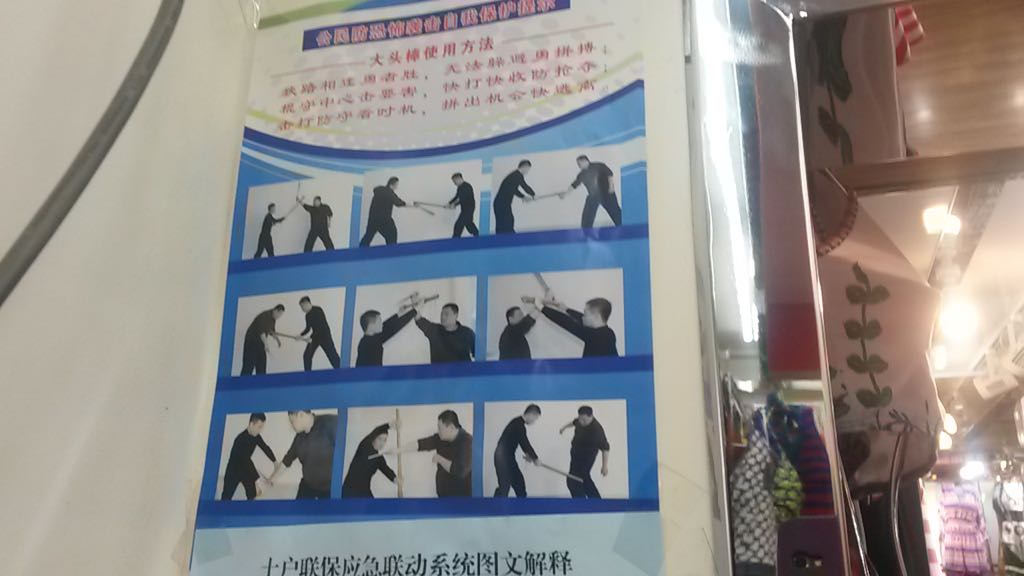

Wang Lechuang, The Villain of the Story

Two days later, Wang Lechuan, Communist Party Secretary of Xinjiang spoke on TV and castigated Uyghurs. He urged Han Chinese to get even. And they did. Armed with axe handles they too rampaged through Urumqi to mete out their revenge. “But how can a leader do this to his citizens?” asked Risalat. “Yes Some Uyghurs did awful things, but where was the legal process? There should have been lawyers, indictments, court cases and transparency. All we saw was kangaroo justice from our window,” she said.

Risalat’s enduring question ten years on, in the light of more disappearances, mass roundups, internment camps, torture and persecution of her people is “why?” “Why are we going through this again? Why does China want to destroy us?”

Her people are broken, torn apart, oppressed and fearing annihilation. “Is it possible for an entire people group to disappear?” she asked. “This is my deepest fear.”