Internment Camps

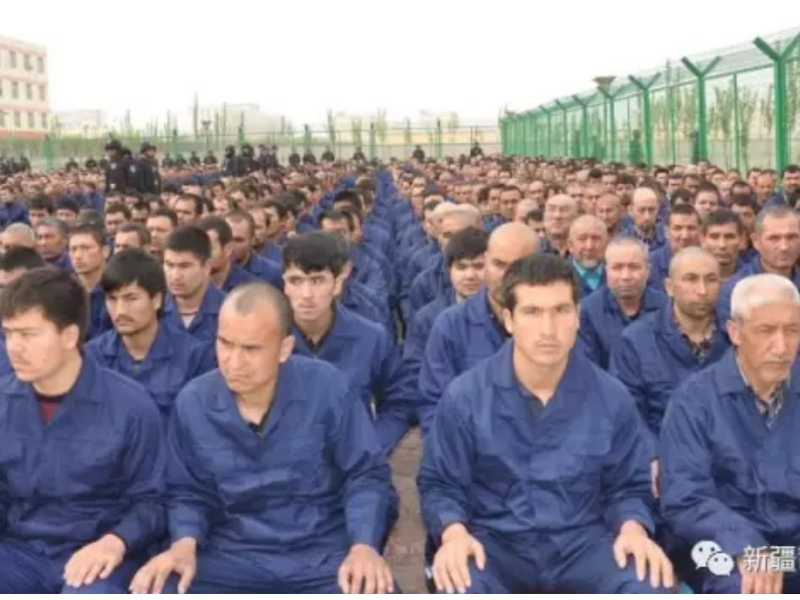

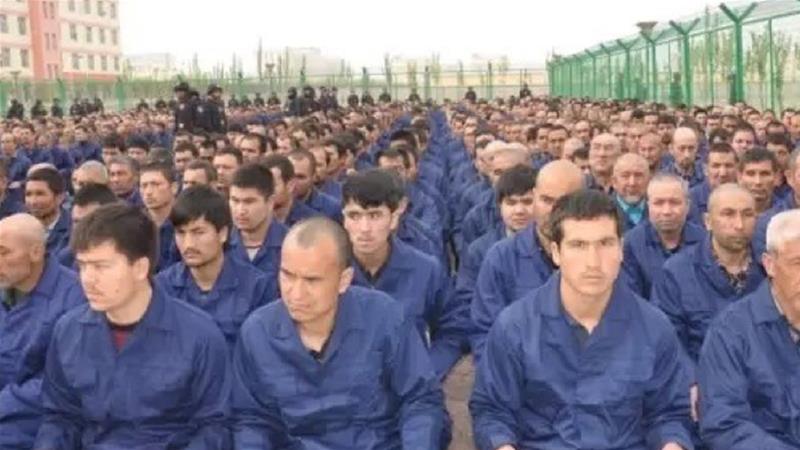

Since April 2017, over 1 million Uyghurs have been rounded up by Chinese police and detained against their will in large internment camps (called ‘reeducation’ camps by the Chinese government) where they have been subjected to arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, political indoctrination, torture and other serious human rights violations. The arbitrary detention of over 1 million people marks a dramatic increase in the China’s oppression of the Uyghur population and the scale and gravity of this act amounts to a crime against humanity.

Overview

In April and May of 2017, Uyghurs living outside China starting losing contact with family members still living in the Uyghur Autonomous Region as thousands of Uyghurs began to be rounded up and sent to the camps. This continued in 2017 as more Uyghurs lost all contact with family members and in 2018 nearly every family in the Uyghur diaspora has a missing relative or loved one.

The political indoctrination camps are in some ways another incarnation of the infamous Chinese work camps (Laogai), but are operated in a more targeted manner with a distinct political purpose. These camps only operate in the East Turkistan and are part of Chen Guanguo’s policies to ‘stabilize’ the region. The camps essentially function as open-air prisons, where detainees are forced to undergo political indoctrination classes aimed at eroding their unique religious, cultural and ethnic identities.

Throughout 2017, the sheer scale and severity what was happening in the camps became apparent. It was reported that in five camps around Kashgar alone, 120,000 Uyghurs were being held.[i] By March 2018, an estimated 880,000-one million Uyghurs are currently being held in these camps.[ii] These number continue to rise, as it was reported in March 2018 that the number of Uyghurs detained in the city of Ghulja has increased substantially. Current estimates (as of May 2019) estimate the total number of detainees to be between 1 – 2 million people. Scholar Dr. Adrian Zenz estimated that 1.5 million people were detained in the camps and the U.S. state department stated between 800,000 – 2 million have been detained. Local authorities in the city have now been given a quota for detentions and authorities have been pressured to detain more people to meet the quota.[iii]

Sophie Richardson, China Director at Human Rights Watch, stated that Uyghurs are being held at these centres, “not because they have committed any crimes, but because they deem them politically unreliable.”[iv] No formal charges are laid against detainees, who are also not provided access to legal remedies, are denied contact outside the camps, and are held for unspecified periods of time. The camps therefore constitute a massive case of state-orchestrated enforced disappearance and arbitrary detention.

Purpose of the Camps

The targeted nature of the arbitrary detentions and the situation inside of the camps reveal that they function as part of a larger campaign of cultural assimilation and ideational oppression aimed at ‘stabilizing’ the Uyghur Autonomous Region by eroding the unique Uyghur ethnicity. This has been in the Chinese government’s treatment of Uyghurs both inside and outside of the camps.

According to the testimony of camp survivors, detainees are subjected to forced political indoctrination in the camps. They are forced to repeat slogans, sing Chinese patriotic songs and swear loyalty to Xi Jinping. Detainees are also forced to denounce their religious beliefs and ties to their Uyghur ethnic identity. In this manner, the Chinese government is attempting to ‘socially reengineer’ the entire Uyghur people and forcibly assimilate them into a Han-Chinese dominated China.

While the Chinese government has attempted to forcibly assimilate the Uyghur people through numerous policies in recent decades, this has escalated dramatically in the last 5 years since Xi Jinping has come to power. As Xi Jinping has sought to eliminate any challenge to his absolute authority, the existence of large, unique ethnic groups such as the Uyghurs and Tibetans have been viewed as a threat and great efforts have been made to control and assimilate the Uyghur and Tibetan peoples. Everything that makes Uyghurs unique has been targeted: language, religion, culture, history and ethnic identity.

Language has been targeted in particular. In the internment camps, former detainees have reported that all those in the camps are required to learn Han-Chinese. In schools, public offices and many other parts of society in East Turkistan, the Uyghur language has been ban or discouraged.

The CCP has also sought to control and eradicate religious sentiment. Restrictive legislation, especially the Regulations on Regulations on Religious Affairs and the Regulation on Deextremification have established complete state control over every element of religious practice. All mosques and imams must be approved by the Chinese government and Uyghurs are banned from conducting any religious activity outside the heavily surveilled, government-approved mosques. Even the most basic expressions of religious sentiment have been banned, including: growing a long beard, wearing an Islamic veil, owning a Quran or prayer mat, sharing or receiving religious messages online, giving Uyghur children traditional Islamic names and teaching children under 18 about religion.

The young Uyghurs have especially been the target of indoctrination efforts, as the CCP seeks to eradicate the Uyghur identity from the next generation. Uyghur children whose parents have been detained in the camps have been taken to state run ‘orphanages’ where they are subjected to political indoctrination from Chinese officials.

According to anecdotal evidence, reports from human rights organisations and testimonies of former detainees, groups that were at particular risk of detention are those deemed to be ‘politically unreliable’ including:

i. Practicing Uyghur Muslims

One of the principle targets of the Chinese government’s strategy to stabilize and culturally assimilate the Uyghur population has been the practice of Islam. The mass incarceration of Uyghurs also forms part of the Party Secretary Chen Quanguo’s ‘de-extremification’ efforts in the region, which has tried to conflate the peaceful practice of Islam and any expression of Uyghur dissent with ‘extremism’ and terrorism. Restrictive legislation has established state control over every aspect of religious practice in the region and young Uyghurs are not allowed into mosques or to be taught about religion by their parents. Since April 2017, Uyghurs accused of harboring “extremist” and “politically incorrect” views have been detained in re-education camps throughout the Uyghur Autonomous Region and are subjected to indoctrination classes where they are forced to denounce Islam and swear allegiance to the CCP. Religious men in particular have been targeted, according to a source who had been detained in one of the camps who was interviewed by the WUC. Cities with a more religious population have experienced greater rates of detention, especially in Hotan[i]and Kashgar[ii].

ii. Uyghurs who have studied abroad or anyone with ties to anyone living abroad

Uyghur students who pursued education overseas have been at particular risk of arbitrary detention in the camp network. In May 2017, Radio Free Asia reported that Uyghurs studying abroad received notice from the Chinese government that they must return home by 20 May 2017[iii]. Families of these students were detained or threatened with detention unless they returned home[iv]. In the July 2017, over 200 Uyghur students were arrested in Egypt at behest of the Chinese government[v]. Over 20 of these students were forcibly returned to China and have since disappeared[vi]. They are likely detained in a ‘re-education’ camp. Many of those who returned home voluntarily were also sent to ‘re-education’ camps, including Abdusalam Mamat and Yasinjan. They had been studying in Egypt in 2015-2016 and had returned to China voluntarily, but were detained immediately on arrival and died in mysterious circumstances in December 2017[vii].

Gulgine Tashmemet, a young Uyghur woman who had been studying in Malaysia disappeared on Decemeber 26th after returning home to see her parents who she had not been able to contact[viii]. She was reported missing by her sister and is presumed to be detained in a camp. Several international media outlets have also reported on the detention and harassment of Uyghur studying abroad. Foreign Policy published an article about Iman, a Uyghur who had been studying in the USA, who was briefly detained in a camp after returning to China to visit his family[ix]. Nathan VanderKlippe from the Globe and Mail interviewed Aynur, a Uyghur student in Canada who was being pressured to return to China and had her two brothers already detained in ‘re-education’ camps[x]. The families of Uyghur students and the Uyghur diaspora still living in East Turkistan are threatened with detention by the Chinese government if they choose to speak to international press or engage in human rights activism.

iii. Leaders, celebrities and prominent figures in the Uyghur community including politicians, businessmen, religious scholars and intellectuals

Leaders, celebrities and prominent figures in the Uyghur community have also been targeted in particular, as the Chinese government aims to silence strong and independent Uyghur voices. Two important religious leaders and scholars, Muhammad Salih Hajim[xi], who was the first to translate the Quran in Uyghur, and Abdulnehed Mehsum[xii]were detained in the camps and later died in mysterious circumstances.

Uyghur celebrities are also currently being detained in the camps. Ablajan Ayup, a well-known Uyghur pop star in East Turkistan, has been missing since 15 February 2018 and is believed to currently be detained in a ‘re-education’ camp[xiii]. He wrote songs about education and the Uyghur identity and had worked to bridge the divide between the Uyghurs and the country’s Han Chinese majority. He may have been detained because he had once travelled to Malaysia. Erfan Hezim, a 19 year old Uyghur who was a pro-football player in the Chinese Super League and former member of China’s national youth football team, was reported to be detained in a camp in April 2018 for travelling outside China as part of his pro-football career[xiv].

iv. Family members of human rights activists, journalists and politically engaged Uyghurs in the diaspora.

In 2017, 30 relatives of noted Uyghur activist Rebiya Kadeer were arrested and sent to the camps, likely because of their affiliation with her.[xv] Two brothers of Dolkun Isa, the President of the WUC, were also sent to the camps and he was not been able to communicate with his elderly parents since April 2017. Sadly, in June 2018, Dolkun Isa received word that his mother had died in a camp under mysterious circumstances. Uyghur journalists have also been targeted, as the relatives of Gulchehra Hoja, a Radio Free Asia (RFA) journalist, disappeared and were presumably sent to the camps.[xvi]Five other journalists at RFA have since come forward saying that their relatives have disappeared into ‘re-education’ camps as reprisals for their work. The families of those in the Uyghur diaspora who are still in East Turkistan are often used as leverage to prevent the diaspora from speaking to the press or engaging in any forms of activism.

v. ‘Two-Faced’ Uyghur public officials and civil servants

There has been a general campaign by the Chinese government to root out ‘Two-Faced’ officials, or any Uyghur public civil servants who do not demonstrate absolute loyalty to the party. Under this scheme, showing sympathy for Uyghur detainees in the camps or failure to zealously implement repressive measures against the Uyghur people is grounds for being labeled ‘Two-Faced’.

Pezilet Bekri, a Uyghur woman in her 30s, was a Uyghur public official in Kashgar, working as the Communist Pary secretary of Kashgar’s Yarbagh Neighborhood Committee, before she was fired for “expressing sympathy” for fellow Uyghurs who were rounded up and sent to the ‘re-education’ camps[xvii]. She was then detained in one of the camps she had previously overseen.

Mapping the Internment Camps

Human rights activists, academics and other governments have tracked the growth and expansion of the internment camps using satellite imagery, witness testimony and trips to the region. Shawn Zhang, a researcher of Chinese origin living in Canada was one of the first to use satellite imagery to map the internment camps in East Turkistan. Since then, Reuters, BBC, ABC, the New York Times and others have used satellite imagery to identity and map the camp system. Estimates on the number of internment camps varies.

The Council of Foreign Relations has confirmed the locations of 27 camps in East Turkistan:

Reuters tracked 39 internment camps facilities in their report and documented their expansion over time:

A report from BBC examined 44 sites and a team from BBC attempted to visit one of the camps in person, but were prevented from accessing it by Chinese police:

An undercover reporter from Bitter Winter captured footage of the inside of an internment camp in the Yingye’er township. The video shows a prison like structure, with surveillance cameras covering every inch of the camp:

Conditions in the Interment Camps

Conditions in the camps are reportedly very poor, with massive overcrowding and squalid living spaces.[vii] Those detained in the camps have regularly been subjected to acts of torture including food deprivation, solitary confinement, the use of a “tiger chair,” a device that clamped down on the victims wrists and ankles and being hung by their wrists against a barred wall. Omir Bekali, a Kazakh Muslim who was held in the camps for 8 months before being released reported being routinely subjected to torture and contemplating suicide during his arbitrary detention.

Many people have already died in the camps, due to medical neglect, torture or other mistreatment. A full list of Uyghurs confirmed to have died in the camps is available below, although the actual number is likely much higher.

- Abdulnehed Mehsum, an 88 year old religious scholar, died while being held in a political indoctrination camp in Hotan prefecture in November 2017, though the death was not reported until May 27, 2018.

- Abdusalam Mamat and Yasinjan – two Uyghur students whose deaths were reported in December 2017.

- Muhammad Salih Hajim, an important Uyghur scholar and religious figure, was reported to have died in a camp in January 2018.

- Tursun Ablet committed suicide in February 2018

- Yaqupjan Naman, a teenager, died under mysterious circumstances in March 2018.

- Abdughappar Abdujappar a 34-year-old father of two died in April 2018

- The death of an elderly Uyghur woman in a camp in Ili Kazakh was reported in May 2018

- Ayhan Memet, the mother of WUC President Dolkun Isa died on 18 May 2018

- 26 Uyghurs, mostly elderly people, were reported to have died in the camps in June 2018

In summary, it is important to note the following:

- There is no warrant or official record of the detainees being arrested.

- Those who are detained in the camps are being held against their will.

- The detention is arbitrary, with no charges levied against those who have been detained and no evidence of any criminality.

- It is not clear how long Uyghurs will be held in the camps, as there is no official documentation, charges or sentencing.

- Those detained have no access to judicial or legal remedies.

- There is no communication between those detained in the camps and the outside world.

- The motivation for detaining these individuals is due to their ethnic, religious and cultural identity.

- Detainees are subjected to torture, poor living conditions and other serious human rights violations, already resulting in over 35 deaths.

Useful Resources on Political Indoctrination Camps:

- ‘New Evidence for China’s Political Re-Education Campaign in Xinjiang’ by Adrian Zenz, Publication: China Brief Volume: 18 Issue: 10, Available at: https://jamestown.org/program/evidence-for-chinas-political-re-education-campaign-in-xinjiang/

-

‘List of Re-education Camps in Xinjiang 新疆再教育集中营列表’ by Shawn Zhang, Medium, Available at: https://medium.com/@shawnwzhang/list-of-re-education-camps-in-xinjiang-新疆再教育集中营列表-99720372419c

-

World Uyghur Congress Universal Periodic Review of China Submission

- World Uyghur Congress Parallel Submission to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) for the People’s Republic of China (PRC)

References:

[i]Hoshur, S. (2018, January 22). Around 120,000 Uyghurs Detained For Political Re-Education in Xinjiang’s Kashgar Prefecture, Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service. Retrieved from: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detentions-01222018171657.html

[ii]Phillips, T. (2018, January 25). China ‘holding at least 120,000 Uighurs in re-education camps’, The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jan/25/at-least-120000-muslim-uighurs-held-in-chinese-re-education-camps-report

[iii]Hoshur, S. (2018, March), Xinjiang Authorities Up Detentions in Uyghur Majority Areas in Ghulja City, Radio Free Asia, available at: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/detentions-03192018151252.html

[iv]Human Rights Watch (2017, September 10). China: Free Xinjiang ‘Political Education’ Detainees, available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/09/10/china-free-xinjiang-political-education-detainees

[v]Amnesty International (2017, November 14). Urgent Action: 30 Relatives Of Uighur Activist Arbitrarily Detained (CHINA: UA 251.17), available at: https://www.amnestyusa.org/urgent-actions/urgent-action-30-relatives-of-uighur-activist-arbitrarily-detained-china-ua-251-17/

[vi]Hoja, G. (2018, February 24). Gulchehra Hoja: I demand Chinese Government Release My Parents, East Turkestan Info. Retrieved from: https://eastturkistaninfo.com/2018/02/24/gulchehra-hoja-i-demand-chinese-govt-release-my-parents/

[vii]Hoshur, S. (2018, January 26). Overcrowded Political Re-Education Camps in Hotan Relocate Hundreds of Uyghur Detainees, Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service. Retrieved from: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/camps-01262018140920.html

[viii]World Uyghur Congress (2018, January 30). Press Release: WUC Deeply Saddened By The Death Of Uyghur Religious Leader, Muhammad Salih Hajim, In Chinese Custody, available at: http://www.uyghurcongress.org/en/?p=33941

[ix]Hoshur, S. (2017, December 21). Two Uyghur Students Die in China’s Custody Following Voluntary Return From Egypt, Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service. Retrieved from: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/students-12212017141002.html

[x]Hoshur, S. (2018, February 5). Threat of Re-Education Camp Drives Uyghur Who Failed Anthem Recitation to Suicide, Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service. Retrieved from: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/suicide-02052018165305.html

[xi]Hoshur, S. (2018, March 14). Uyghur Teenager Dies in Custody at Political Re-Education Camp, Radio Free Asia Uyghur Service. Retrieved from: https://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/teenager-03142018154926.html