International firms are benefiting from Chinese technologies used to persecute Uyghurs

Minority Rights, 05 October 2020.

Below is an article published by Minority Rights. Photo New York Times.

In November 2019, the United States (US) Commerce Department blacklisted 28 Chinese entities for their role in the ‘implementation of China’s campaign of repression, mass arbitrary detention, and high-technology surveillance’ in Xinjiang. The list of banned firms now includes the regional Public Security Bureau, subordinate government agencies and a number of commercial firms, including Hikvision, Dahua Technology, iFlytek, Yixin Science and Technology Co. and others. Many of these entities are either wholly or partially state-owned and at the centre of China’s rapid development of surveillance infrastructure.

Hikvision, the world’s largest video surveillance firm, has many contracts with police in Xinjiang, including security cameras at some of the internment camps where over 1 million Uyghurs have been forcibly detained, as well as big data centres and drone operations. In fact, since Chen Quanguo, the architect of these mass surveillance and detention policies, assumed the role of Xinjiang Party Secretary, a position he had previously held in Tibet, Hikvision and Dahua Technology have won more than US$1 billion in government contracts in the region. Despite this, and even as the US was banning Hikvision for its role in human rights abuses, news reports were emerging that the US government had itself been a repeat customer, with thousands of the cameras produced by these companies still installed in military facilities across the country.

Huawei, the telecommunications giant embroiled in numerous legal battles with the US over espionage and national security concerns, likewise has extensive government contracts with the Public Security Bureau in Xinjiang, including the establishment of an ‘intelligent security industry’ innovation lab. However, Huawei has previously misrepresented the extent of its partnerships with the security sector in the region to hide involvement in human rights violations. This happened, for example, before the British House of Commons in June 2019 and, despite these human rights concerns and pressure from its intelligence allies, in January 2020 the British government initially announced it would allow Huawei a limited role in the development of 5G networks in the United Kingdom (UK). It then reversed its stance in July 2020, following new sanctions imposed on Huawei by the US government in May. However, the British change of heart was not motivated by Huawei’s involvement in Xinjiang, but rather by other diplomatic and domestic security concerns. Other Chinese technology firms involved in Xinjiang include Megvii Technology, SenseTime and ByteDance, which is the parent company of the popular video-sharing app TikTok.

A November 2019 leak of internal Communist Party documents, obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, reveals how many of these companies are using big data and AI to perfect new forms of repression. Machine learning, a driver of AI, thrives on data, and for surveillance technology this is often biometric data such as photographs for facial recognition, or fingerprints, iris scans, voice recordings and DNA samples, all of which have been forcibly mass collected from Uyghurs and other minorities across Xinjiang and elsewhere in China. In this context, Xinjiang has become a laboratory of sorts for the Chinese government: in other words, the mass internment of Uyghurs and other minority groups is both fuelled by the rise in technology and feeding into its evolution in an authoritarian feedback loop.

The technologies tested on and used against minority populations in Xinjiang and across China are also increasingly being deployed outside the country. As China rushes to be the world leader in AI, for example, it has taken to exporting its knowledge and tools. According to Freedom House, out of some 65 countries it surveyed in 2018, 18 were exploiting Chinese AI technology to control and monitor their populations. Many, unsurprisingly, are also countries with poor human rights records of abusing their ethnic and religious minority or indigenous populations, from Pakistan to Zimbabwe. In January 2019, Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro sent a delegation to China to learn about surveillance technologies, and discussed a bill to make facial recognition surveillance compulsory. Worryingly, the Chinese firm Cloudwalk has agreed a deal with the Zimbabwe authorities, whereby it will receive the biometric data of millions of Zimbabweans in order to help improve the recognition of persons with darker skin tones by its AI technologies. This will strengthen China’s own surveillance technologies, as well as those of other governments that are clients of the firm.

At the same time, companies and universities from countries that supposedly respect human rights have contributed to the development of, or made economic investments in some of these technologies. This arguably makes them parties to human rights violations.

Global accomplices: the US and European firms benefitting from human rights abuses

The United Nations (UN) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights call on businesses to prevent and mitigate the actual and potential human rights abuses associated with their business practices, with additional international frameworks placing further emphasis on technology and human rights.

In May 2019, for example, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) adopted Recommendations on Artificial Intelligence, citing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which establishes the rights to privacy, freedom of religion or belief, and prohibits discrimination and arbitrary detention, among others. China, as an OECD member, however, has not endorsed these recommendations.

Because of mounting evidence of actual human rights abuses associated with these technologies in Xinjiang, and arguably the difficulty of separating legitimate technological developments by many Chinese firms from their potential for abusive applications, it is almost impossible for any such partnerships or investments not to be in violation of human rights standards. And yet many firms in the US and Europe have done business with these Chinese technology entities, profiting from what the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination has called a ‘no rights zone’.

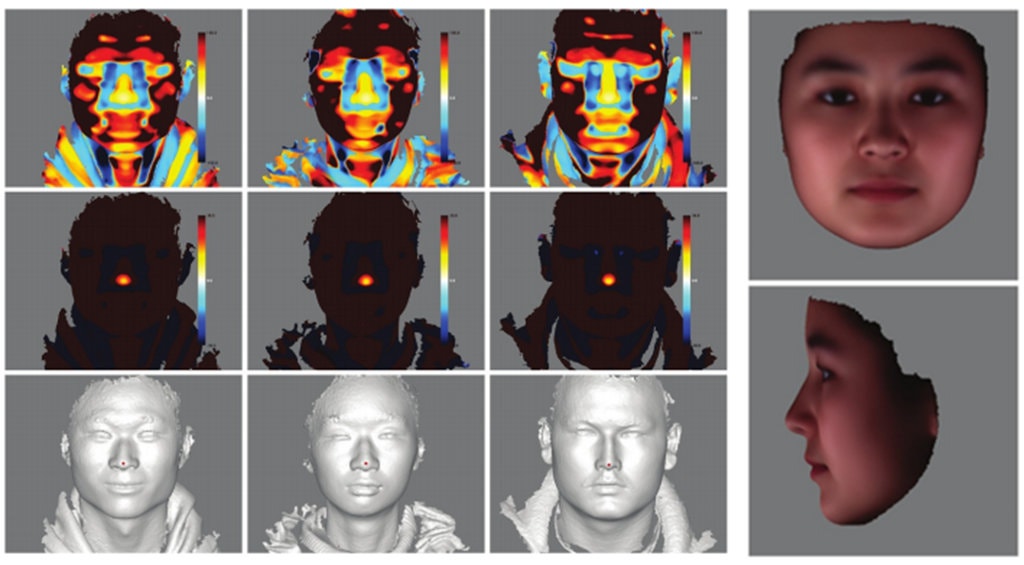

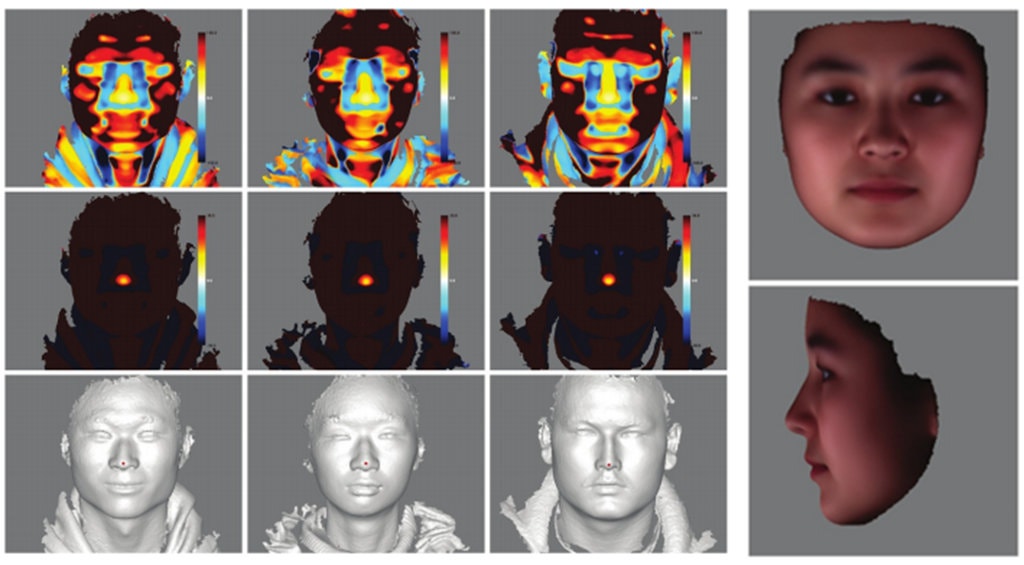

In February 2019, Massachusetts-based biotechnology firm Thermo Fisher Scientific announced it would end sales of its genetic sequencing equipment in Xinjiang but does not appear to have stated conclusively whether it will end sales of its products to other areas in China. Thermo Fisher is not alone in assisting China with DNA sequencing. Yale University School of Medicine Emeritus Professor Kenneth Kidd has also collaborated with the Chinese Ministry of Public Security in Uyghur-targeted genetic research, but claimed he thought the genetic data had been sampled with consent. Although Kidd’s research partnership with the Chinese government had begun in 2010, before mass internment, even a cursory understanding of China’s abusive policies towards minorities should have raised red flags concerning the nature of such collaboration. The German Max Planck Society has also supported genetic research in China. Although they are no longer involved in this research, the negative impact has already been done. China, for its part, has used the genetic technology and skills it has developed in partnership with these groups to experiment with predictive technologies capable of determining from a DNA sample whether someone is a Uyghur, and even to produce a computer-generated map of that person’s face.

At the same time, through companies like iFlytek, Megvii and SenseTime, China has developed advanced AI voice and facial recognition technologies to monitor and control the Uyghur population. Again, such firms have also entered into partnerships with Western institutions. For instance, in 2018 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) launched research partnerships with iFlytek and SenseTime, both of which have since been blacklisted in the US over human rights concerns. In February 2020, MIT cancelled its partnership with iFlytek, but did not say why: although it announced in October 2019 that it was reviewing its partnership with SenseTime, at the time of writing it appears to still be under review.

The German technology powerhouse Siemens has a branch office in Urumqi, the Xinjiang capital, and maintains an advanced technology ‘strategic cooperation’ with China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC), a state-owned military contractor which happens to own a significant stake in Hikvision. CETC is also behind the development of a major predictive policing system identified in a May 2019 report by Human Rights Watch as one of the main systems used for mass surveillance and detention in Xinjiang.

The American firms Seagate Technologies and Western Digital Corp have sold hard drives to Hikvision and other surveillance firms operating in Xinjiang but have denied their culpability, with one Western Digital spokesperson claiming that, while they recognized ‘the gravity of the allegations related to surveillance in the Xinjiang Province’, the company did not sell its products to the Chinese government. This defence is hollow in light of the responsibilities of these firms under international human rights frameworks to mitigate actual and potential human rights abuses associated with their business practices, given the impossibility of separating the actions of private and state-ownedfirms in the context of China.

Similarly, Hewlett Packard owns nearly 50 per cent of New H3C Technologies Co. Ltd, which develops tools for law enforcement, with a November 2019 Wall Street Journal report identifying several internment camps in Aksu as customers of this technology. But while a spokesperson for Hewlett Packard Enterprise confirmed that IT equipment had been sold to authorities in Xinjiang, it attempted to distance itself, noting it was not aware of specific transactions and would be looking into it.

China’s development of abusive technologies has not only been fuelled by partnerships with technology firms and researchers, but also investments from Western financial institutions. In March 2019, the Financial Times revealed that two major American pension funds, the California State Teachers’ Retirement System and the New York State Teachers’ Retirement System, owned tens of millions of US dollars’ worth of shares in Hikvision.

Likewise, other major international investment firms such as Fidelity International, Aberdeen Standard Investments and Schroders, as of late 2019 held shares worth more than US$800 million in Hikvision and Dahua. Hikvision’s own website, furthermore, lists banks UBS and JP Morgan as among the company’s top 10 shareholders. And a 2017 market research report by Deutsche Bank explicitly listed the likelihood of Dahua Technology securing a ten-year government-backed tender – for ‘a safe city project, which includes infrastructure as well as a public video sharing platform’ – as the reason for its ‘buy’ rating.

While these firms may pay lip service to human rights due diligence in selecting their investment portfolios, many major investment firms remain, at the time of writing, shareholders in these companies, despite their being sanctioned by the US government – and in the face of rampant evidence of their technologies being used to carry out gross human rights violations.

What is to be done

China’s current development and use of AI and related surveillance technologies, especially in Xinjiang, not to mention the sale of these technologies or exchange of knowledge that may contribute to abuses elsewhere, violates existing and evolving international norms and standards on technology and human rights. Foreign enterprises, investment firms and research institutions in the UK, US and elsewhere cannot continue to proclaim their ignorance of the abusive applications of these technologies in view of the mounting evidence of widespread targeting and persecution of minority populations in China, particularly Xinjiang. Those who continue to engage in business or to invest in these companies must accept their culpability in the human rights violations being carried out there at this very moment: not only the monitoring and surveillance of whole cities and their Uyghur residents, but the even worse abuses being carried out unseen in the darkness of China’s internment camps.