At least 238 writers and intellectuals were detained for their work last year, advocacy group says

The imprisonments and detentions occurred in 34 countries, although the majority took place in just three — China, Saudi Arabia and Turkey. Those same countries are also among the top jailers of journalists worldwide, according to the 2019 Committee to Protect Journalists prison census.

The data published Tuesday as part of PEN America’s inaugural Freedom to Write Index accounts for poets, scholars, songwriters and translators, among other intellectuals the group described as unjustly detained last year around the world. It does not include journalists unless they also belong to one of the categories in question. Some detained individuals were excluded from the report at the request of family members who feared that public attention could worsen their situations.

“Part of the basis for inclusion here is a consensus among organizations like ours that the charges are spurious,” said Summer Lopez, senior director of PEN America’s free expression programs. To be included on the list, the organization concluded individuals were “being targeted because of their expression, or activism due to their writing” and had spent at least 48 hours behind bars in 2019.

PEN America, which tracks threats against writers worldwide, said it launched the index and a new Writers at Risk database to illustrate a growing trend of government leaders clamping down on creative thinkers and intellectuals in an “attempt to quash criticism, clamp down on independent voices and gain control of cultural and historical narratives.”

Through their work, writers and intellectuals often offer new perspectives and pave the way for “citizens in repressive societies to envision a different future,” the report said.

They are also often among the first to be “targeted when a country takes a more authoritarian turn,” Lopez said. “We felt this was kind of a missing piece of this advocacy work on behalf of writers, and I think having that number can be very powerful.”

Karin Deutsch Karlekar, director of PEN America’s free expression at risk programs, said that the data, compiled in large part through PEN’s expansive international network of writers and advocates, revealed an alarming number of writers and public intellectuals are being intimidated and detained around the world. More than half of all those detained last year faced national security-related charges.

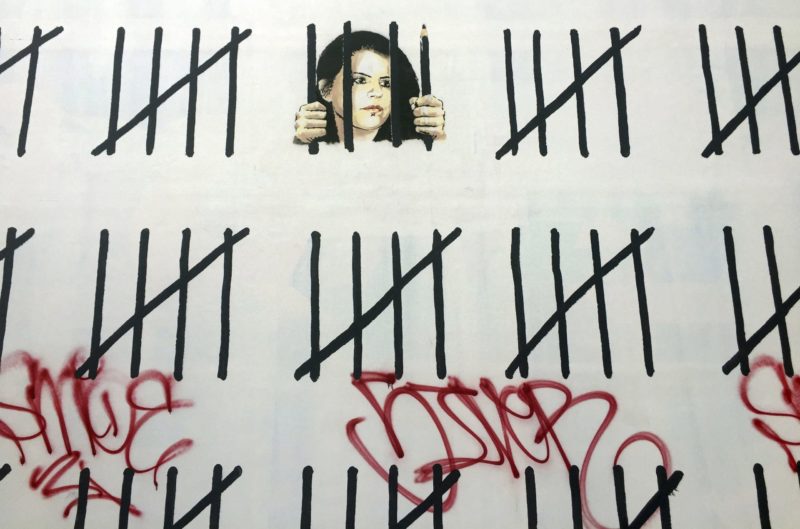

All 30 Turkish intellectuals included in the index faced such charges, the PEN researchers found. Among them was Zehra Dogan, a Kurdish artist and journalist charged in 2017 over a painting of the Turkish city of Nusaybin in the country’s southeast, the site of clashes between the Turkish military and the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) in 2016. She was released in February of last year.

Many of those targeted globally belonged to minority ethnic groups, the researchers found.

“There’s a particular focus on writers writing in ethnolinguistic minority languages, and they were particularly targeted in these countries where there are broader crackdowns,” Karlekar said, citing the detention of Uighurs in China, along with people writing in Kurdish in Turkey and Iran.

Out of the 73 people in China included in the index, 32 were being held in China’s western Xinjiang region, where the Uighur minority faces widespread surveillance and at least a million people have been detained for “reeducation.” PEN America described the number of people detained there as “likely an underestimate.”

Women detainees make up just around 16 percent of the total count, but a disproportionate number of women detained were actively working to advance women’s rights, PEN America found. Among those included in the group’s count is Loujain al-Hathloul, a Saudi writer and women’s rights activist currently behind bars.

Hathloul was detained in 2018 as part of a larger crackdown on activists in the kingdom. Her family alleges she has been tortured while in custody. Last summer, her brother tweeted that she was offered freedom in exchange for signing a document and appearing in a video claiming she had not been tortured.

“She immediately ripped the document,” her brother wrote.

Hathloul previously served time behind bars in Saudi Arabia for attempting to drive into the country from the United Arab Emirates in 2014. At that time, women were banned from driving in Saudi Arabia.

Karlekar said she was particularly concerned to see India, the world’s largest democracy, on the list as one of the top 10 jailers of writers and intellectuals.

“It’s really the only more democratic country on that list,” she said.

At least five writers or intellectuals were detained last year in India, according to PEN America, but the country also accounted for more than a third of cases in which an intellectual was continually harassed by state or nonstate actors — a factor the organization also monitors. Intellectuals in India have faced increasing pressure since Prime Minister Narendra Modi was elected in 2014, the group found.

Since Modi’s reelection last year, the report said, officials “have attempted to purge all manifestations of ‘anti-national’ thought from the national discourse and academia, and have weaponized government bureaucracy and pro-government media and social media trolls to attack critical writers, intellectuals, journalists and commentators, and activists.”

Although around one-third of those included in the global index have been released from behind bars, Karlekar said many “are really in a state of quasi-freedom and not able to resume their life or their work without fear of reprisal.”

But the organization remains “distressed at the number of people still in prison and the potential risks of people in various detention facilities,” Lopez said, particularly as the coronavirus pandemic continues to spread globally. “There is a particular urgency around getting people out of prison.”