Fears for Uyghur comedian missing amid crackdown on cultural figures

The Guardian, 22 February 2019

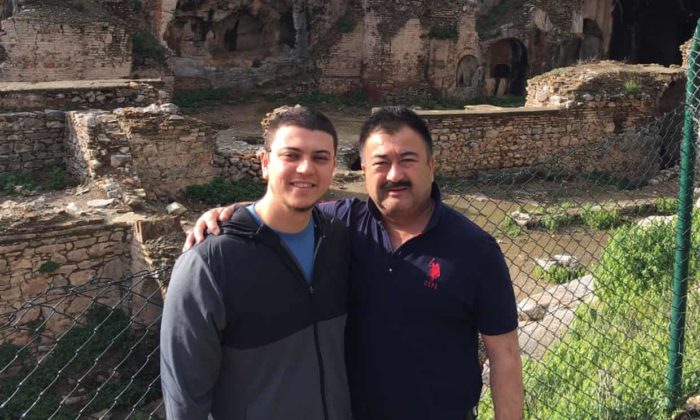

By Kate Lyons and Lily Kuo – Arslan Mijit Hidayat says there is not a single Uighur who has not heard of his father-in-law, Adil Mijit. “We have a saying in the Uighur language ‘From seven to 70’ and anyone between these ages would know him,” said Hidayat, 31, who was born in Sydney to Uighur parents. “He’s A-list. When you think comedy, you think him.”

By Kate Lyons and Lily Kuo – Arslan Mijit Hidayat says there is not a single Uighur who has not heard of his father-in-law, Adil Mijit. “We have a saying in the Uighur language ‘From seven to 70’ and anyone between these ages would know him,” said Hidayat, 31, who was born in Sydney to Uighur parents. “He’s A-list. When you think comedy, you think him.”

Mijit, 55, spent 30 years performing in plays and operas for a government arts troupe in Xinjiang, the far-western Chinese territory home to some 12 million Uighurs. Hidayat compares him to Adam Sandler, Jim Carrey and Australian comedian Carl Barron.

For decades he has been a household name who was known wherever he went in Xinjiang – but no one has seen him for more than three months.n

“My second daughter was born on 1 November,” said Hidayat, over the phone from Istanbul, where he lives with Adile, Mijit’s daughter, their children, as well as Adile’s mother and brother. “We got in contact and he was very relieved the birth went well, but from 2 November we didn’t hear any news.”

They believe Mijit has been taken, like an estimated one million others, into one of hundreds of detention centres that have been built by the Chinese government in Xinjiang over the past few years. China’s ministry of foreign affairs did not respond to questions about Mijit’s whereabouts.

Beijing defends the camps, calling them “vocational training centres” where students are taught Mandarin, Chinese law, and vocational skills. According to accounts from ex-detainees and relatives of those sent to the camps, they are de-facto prisons where their mainly Muslim inmates are subjected to political indoctrination, arbitrary detention, as well as psychological and physical abuse.

For years, authorities have cracked down on expressions of Muslim and Uighur culture, with bans on headscarfs, beards, and traditional Uighur dress. Officials have launched an “anti-halal” campaign while mosques are closely surveilled or torn down. China says these restrictions are to guard against Islamic extremism and separatism.

Now, authorities appear to be targeting prominent Uighur cultural figures. “It is apparent that there is a deliberate policy of targeting cultural leaders: writers, academics, artists, adding weight to the charge of cultural genocide,” said Rachel Harris, a researcher focused on Uighur music and culture at SOAS University of London.

Among those who have disappeared are Sanubar Tursun, a well-known folk singer, Rashida Dawut, a pop star, singer Zahirshah, who got her start on a popular singing competition, Voice of the Silk Road, poet Ablikim Kelkun, folk and pop singer Paride Mahmut, and Ablajan Ayup, a pop singer dubbed the “Uighur Justin Bieber”.

Harris says the detentions of people like Mijit devastate the Uighur community at large. “There is very great fear that what is under attack here is Uighur identity, language and culture. They fear there is a project to erase that identity, and it is something they hold very dear. So when people like [Mijit] are detained, they have immense symbolic power,” she said.

Earlier this month, Chinese state media released a video of famous Uighur musician Abdurehim Heyit who had disappeared in 2017, to dispel rumours of his death. In the video, Heyit attested to his health and said he had “never been abused”.

Instead of the calming outcry, the video prompted Uighur families around the world to call for similar proof-of-life videos from their loved ones under the hashtag #MeTooUyghur. Mijit’s family have launched a similar campaign under the hashtag #FreeAdilMijit.

The voices from Uighur relatives add pressure on Beijing, which is facing growing international criticism over Xinjiang.

Mijit’s case is also remarkable because of his connections with the government – a sign, advocates say, that no one is safe. As a performer with a state troupe, he was an employee of the government for almost 30 years.

Mijit and his family believed his longtime government connections would protect him.

“We thought he was untouchable… If we knew there was even a 1% chance, I would have ripped up his passport and said: ‘Sorry mate, you are staying with us’,” Hidayat said.

Mijit’s passport was seized by officials when he returned to China from visiting his family in Turkey in June 2017. During that visit, Mijit told his relatives that his colleagues had started disappearing and that government officials had come to his office and handed out forms, forcing people to tick a box saying whether they were Muslim.

The family had urged him to stay with them in Turkey. Mijit insisted on returning to Xinjiang.

“He said: ‘Look the situation is so bad, I need to be there to cheer my people up,’” said Hidayat. “He loved his people. It didn’t sit right with him, he would feel guilty [being free] while his people are being persecuted. He felt like he owed it to them to be there to the end.”