Uyghur Journalist Reports on Own Family’s Disappearance, Fights for Release

The Epoch Times, 10 December 2018

ByGulchehra Hoja had a childhood full of dance and music in Xinjiang, China. She loved being on camera and dreamt of becoming a TV host. And she did. Hoja hosted shows in Chinese and the Uyghur language and started the first-ever children’s show on Xinjiang TV. She was a known face for Xinjiang viewers.

ByGulchehra Hoja had a childhood full of dance and music in Xinjiang, China. She loved being on camera and dreamt of becoming a TV host. And she did. Hoja hosted shows in Chinese and the Uyghur language and started the first-ever children’s show on Xinjiang TV. She was a known face for Xinjiang viewers.

In 2001, while on vacation in Europe, she heard something she’d never heard before—an uncensored news report on the radio about a protest in Xinjiang.

She decided not to go back and to work as an Uyghur-language journalist from the outside instead. She got a job with Radio Free Asia (RFA) in Washington, a broadcaster that brings free information to areas of Asia that don’t have freedom of the press. Her viewers became her sources and helped her with information about the persecution of Uygurs by the Chinese communist regime.

It’s now 17 years since Hoja has been reporting on the plight of Uyghurs in communist China. But never in her wildest dreams did she think that one day she would have to talk about the persecution of 25 family members of her own, including, tragically her baby brother.

“He’s just one-and-half-years younger than me. I feel he’s remembering me. I dream about him almost every night. I feel his suffering. I’m too suffering from this separation but he’s suffering more,” said Hoja.

Hoja has fond memories of her only sibling, Kaisar Keyum. They went to school together and never parted as kids. “Whenever I fell sick, he wouldn’t leave me. If I didn’t go to school, he also refused to go,” Hoja said. Their names have similar meanings, while Gulchehra means “one with a flower like a face,” Kaisar means “the saffron or the saffron flower.”

When Hoja joined RFA, Keyum was in college. She never went back home again and that changed Keyum’s life forever. Regular police interrogation forced him to drop out of school so he had to get a job as a translator.

“Twice [potential] marriages didn’t happen because the police came to the girls’ families and asked things like, do you know his family’s background. Why would you want to be in trouble?” said Hoja.

Keyum has been arrested a total of about 10 times, the last time on Sept. 28, 2017. He’s still in jail.

Hoja was in shock and tears when her mother, Qimangul Zikri told her that the police blamed Hoja for Keyum’s arrest. Panicked, Zikri quizzed police about why, to which the officer replied, “His sister works there [RFA], is that not enough for taking him? ”

The Chinese regime crackdown on Uyghurs has intensified since 2016. Around 1 million Uyghurs are detained in various pre-trial detention centers and prisons, both of which are formal facilities, and in political education camps, which have no basis under Chinese law, according to Human Rights Watch.

In April 2017, the Chinese Communist Party introduced the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region De-Extremism Regulations. According to Chinese Human Rights Defenders (CHRD), a network of Chinese and international human rights NGOs, these regulations address the Chinese regime’s perceived threat of terrorism linked to extremism.

“Under these regulations, someone can be locked up in a ‘re-education’ camp or forced to attend indoctrination sessions for possessing certain halal products, having a long beard, wearing a full-face headscarf, selecting children’s names with ‘Islamic connotations,’ refusing to consume state television or radio, or refusing to break Islamic dietary restrictions,” said CHRD.

Re-education camps are the Chinese regime’s long-standing practice to eradicate any group that doesn’t match its communist ideology. A 2018 report by the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination by 18 independent experts, cited credible reports of widespread torture of ethnic groups in Chinese re-education camps. The persecution of the spiritual practice of Falun Gong and House Christians is also widely reported.

The disappearance of Hoja’s Family

On Feb. 3, Hoja received another shocking phone call from her neighbour’s daughter: “Did you hear, sister, your parents, all your family members, 25 people, are arrested by the Chinese government on the same day.”

“I was shocked. I couldn’t believe it. I said, ‘Why? How do you know?’ She said, ‘I know because my mum told me.’ And then I just immediately called up to my home and nobody picks up. I called my father, mother, her phone, my brother, my cousins, like around 30 people, nobody picks up the phone,” Hoja said.

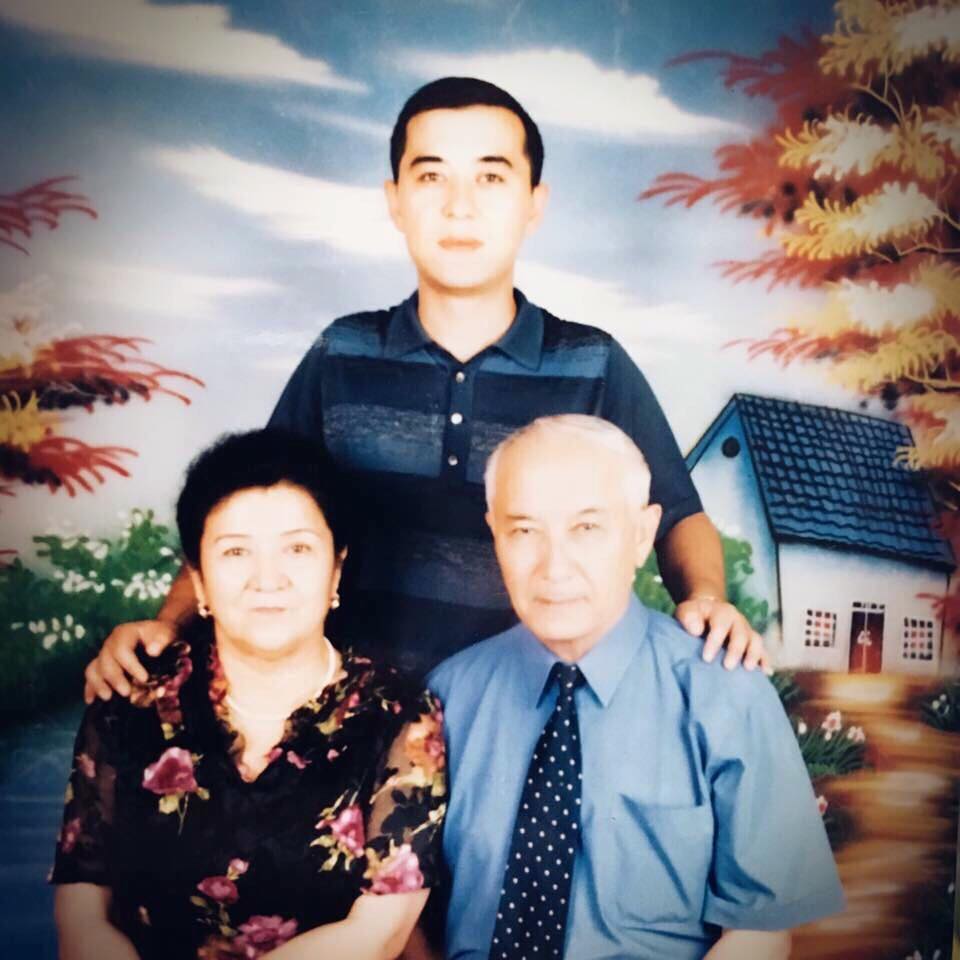

Teary-eyed Hoja sits on a chair in the dining room. Just behind her, in the living room, dry fruits, cookies, chocolates sit on a table, ready to be served with etken chai (Uyghur tea). In the corner to the left, is a picture of her parents and to the right is another frame of her brother in a suit and a bow tie.

“I can’t describe my feeling at that time. It’s huge guiltiness, you know. It’s because the phone [call] said because of me they have been arrested. But I feel so helpless and even I don’t know where they are taken, are they alive or not!”

Zikri was released on March 10 but others are still under arrest, including Gulchehra’s 77-year-old father who is half-paralyzed after a stroke and was placed under guard in his hospital room.

Since the arrests, Hoja has spoken at various forums across the United States about her family’s predicament. She also testified before Congress in July. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have reported on her family’s case and the media world over have written about her fight for justice.

But the pain inside her refuses to subside. She worries about her old aunt who is left to take care of three small grand children alone. Every time she cooks kababs in her kitchen she remembers Keyum.

“His picture is on [my] desk every day, in my heart actually! I wish to see him. If he appears before me, I’ll not stop to kiss him and I’ll say ‘I’m sorry!” said Hoja.

As for her home in Virginia where Gulchehra lives with her husband and three children, there’s a glass case full of Uyghur memorabilia including a stone that her father sent to her. She believes he sent a stone because letters are always under surveillance. By sending her a stone, her father sent her a strong reminder to remain connected with her people and her culture.